Home | Publications | Presentations | Teaching | Contact

Academic Presentations

September 2025:

‘Elizabeth I on Tour: Progresses and Pageantry for the Virgin Queen’

Centre for the Study of the Renaissance 2025 Study Day: Elizabeth and the Elizabethans

This session will focus on the progresses Elizabeth undertook every year of her reign. A ‘progress’ is a formal term for the periods when the Queen travelled around her kingdom, visiting various towns and aristocrats. For many places, a progress might be the only time the Queen visited them, and so they sought to capitalise on her presence by lavishly entertaining their now-present sovereign. The iconography of the ‘Virgin Queen’ first appeared in a civic entertainment, which is a reminder that they are essential to understanding the politics and culture of Elizabethan England. As part of this session, attendees will be able to engage with the published accounts of some of these progresses and the pageantry staged for Elizabeth.

★ ★ ★

July 2025:

‘Connecting with the Biblical Past: Women Poets of the Seventeenth Century and the Old Testament’

Society for Renaissance Studies 11th Biennial Conference

When Hester Pulter compared the imprisoned Charles I to the Old Testament figure Job, she was not only emphasising the paramount place of the Bible in the premodern world, but was also engaging with a powerful tool of conceiving the present that was widely employed across Europe. Many women poets of the seventeenth century, including Anne Bradstreet, Katherine Philips, and Pulter, embedded biblical themes and motifs throughout their work in ways that are often overlooked today. These women experienced and viewed the world in very distinct ways, but despite their manifold differences, they were all connected through their reliance on the Bible to comprehend the tumultuous middle decades of the seventeenth century. This paper seeks to unpick some of the ways that the Old Testament was used to understand an array of deeply personal and emotive issues, ranging from the Regicide to the death of a child. In doing so, it seeks to reinforce the status of Bradstreet, Philips, and Pulter as important contributors to seventeenth-century English literature and acknowledges the unique insight into the period that their poetry provides.

★ ★ ★

June 2024:

‘Deborah’s Odyssey in Early Modern England’

The Past is a Female Country: Ancient Women and their Reception in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

Judges 4 and 5 of the Old Testament recount the remarkable story of Deborah, who God chose to lead the Israelites and to deliver them from the oppression of the Canaanites. While the historicity of the Book of Judges is questioned, it is nevertheless significant that one of only fourteen judges was a woman, and Deborah’s example showed that God could—and did—choose women to carry out His plan. Deborah had a long afterlife, and her example was invoked in an array of contexts in succeeding centuries. This paper will analyse some of the many depictions of Deborah in early modern England, with an emphasis on their use in royal iconography during the reigns of Mary I and Elizabeth I, and will seek to show that Israel’s only female judge was a powerful and adaptable figure in the hands of early modern writers and commentators.

★ ★ ★

May 2024:

‘Feminist Intertextuality in Taylor Swift’s Songs’

‘Fuck the Patriarchy’: A Taylor Swift Conference

When Harvard University and Queen Mary University of London announced new modules devoted to Taylor Swift in late 2023, many of the responses were both predictable and unoriginal. What many of the commentators bemoaning the apparent decline in academic standards that such modules represented failed to recognise, however, is that these modules acknowledge that the lyrics of Swift’s songs (in particular) have a clear literary merit that warrants academic study. Such studies, which will hopefully only proliferate, underscore the richness of Swift’s song writing and the under-appreciation of the multi-layered and incisive socio-political commentary evident in her songs. Paying close attention to her lyrics demonstrates that Swift is a consummate adapter, taking a variety of references and deploying them to further her feminist and inclusive agendas. This intertextuality pervades her work: some are more obvious, such as the re-working of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in ‘Love Story’, but many are fleeting, such as the biblical allusion to Moses in ‘Now That We Don’t Talk’, which means that the true extent of Swift’s radical intertextuality is often overlooked. By considering some of the literary, historical, and biblical references in Swift’s oeuvre, this paper argues that Swift’s feminist intertextuality both heightens the literary merit of her lyrics and, most importantly, encourages her listeners to challenge patriarchy, bigotry, and prejudice wherever they find it.

★ ★ ★

May 2024:

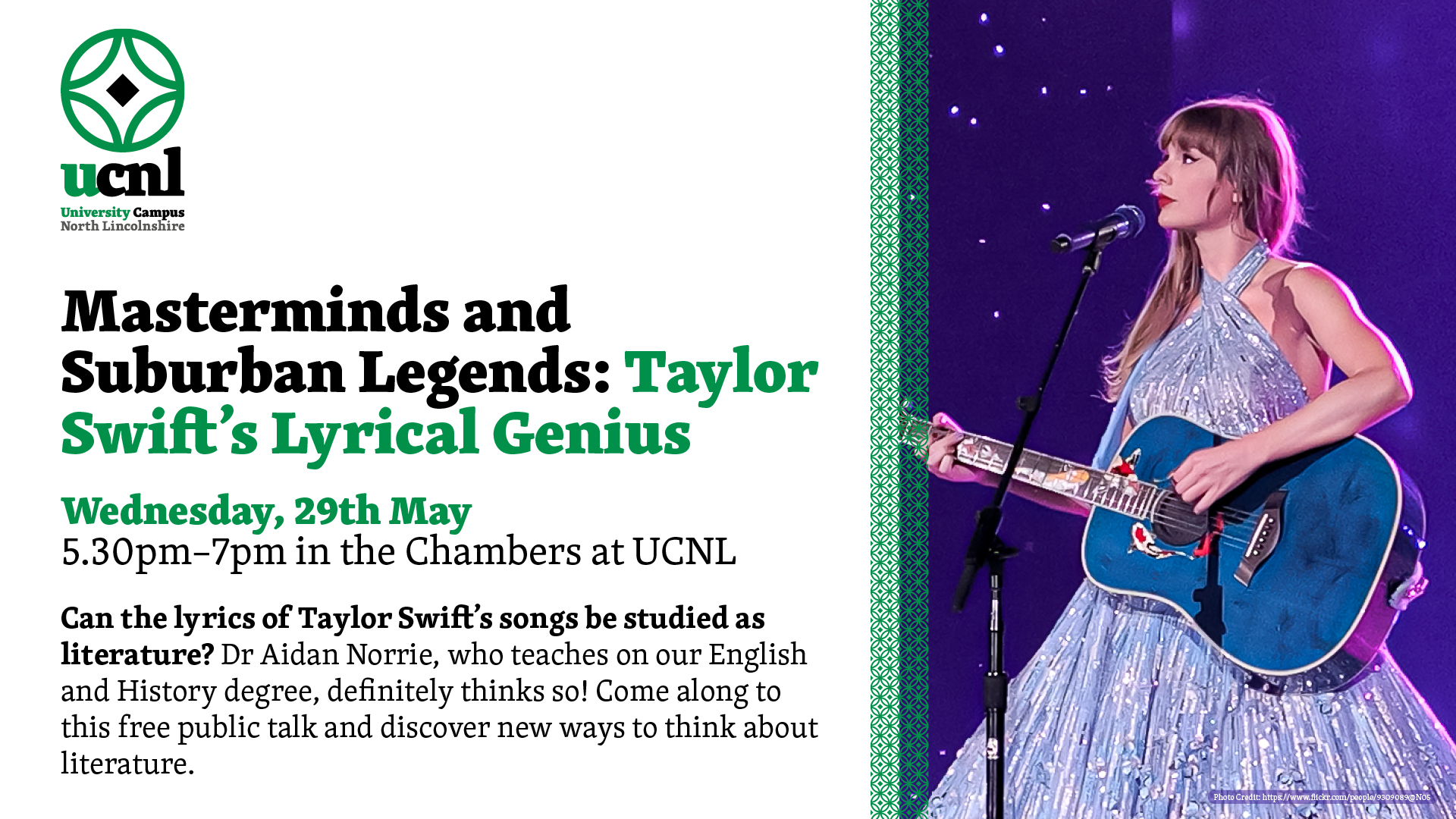

‘Masterminds and Suburban Legends: Taylor Swift’s Lyrical Genius’

Public lecture delivered at University Campus North Lincolnshire

★ ★ ★

June 2023:

‘Biblical Typologies and the 1603 English Succession’

Kings and Queens 12: Royal Success(ion)

When Elizabeth I of England died on 24 March 1603, her cousin, James VI of Scotland, succeeded her. He was her closest living relative according to the normal rules of primogeniture, and James’s descent from Henry VIII’s sister Margaret was widely used to explain James’s claim. Yet, as a variety of scholars have shown, the 1603 succession was neither as smooth nor guaranteed as contemporaries tended to claim. Issues concerning the status of Henry VIII’s will, which privileged the children of his young sister Mary over those of Margaret, James’s status as a ‘foreigner’, as well as the complications arising from fact that Elizabeth had executed his mother for treason, remained unresolved at Elizabeth’s death. Seeking to quickly ingratiate themselves with the new regime, a range of commentators and pamphleteers turned to the Bible to explain the succession, using a variety of biblical typologies to explain that James was England’s rightful king. A common example was to use the succession between David and Solomon: Solomon, who was not David’s eldest son, was chosen by God to succeed his father, meaning that in the present, the Davidic Elizabeth had been succeeded by the Solomonic James. This was not the only biblical example applied to the succession, however, and the various types used—such as Gideon succeeding Deborah—indicate that contemporaries were concerned about James’s confessional identity and the legacy of his executed mother, the (in)famous Mary, Queen of Scots. This paper considers the various biblical typologies employed, showing that they were used to emphasise the purported role of providence in the succession and elide any issues—religious, political, or cultural—that came from an English Tudor being succeeded by a Scottish Stuart.

★ ★ ★

March 2023:

‘When Elizabeth I met Deborah the Judge; Or, I Wrote a Book... Now What?’

Public lecture delivered at University Campus North Lincolnshire

★ ★ ★

November 2021:

‘Remembering Elizabeth I in Seventeenth-Century England’

Public lecture hosted by Education Evolved

Elizabeth I of England remains one of the most familiar figures from English history. This fame is largely the result of the way the last Tudor monarch was remembered and invoked throughout the seventeenth century. This seminar will focus on the uses of Elizabeth’s memory in seventeenth-century England, unpicking the various ways that Elizabeth cast a long shadow over religio-political culture during the reigns of her Stuart successors. Utilising both historical documents and literary texts, this seminar will show that ‘Good Queen Bess’ was a powerful touchstone for contemporary concerns, and will emphasise the way Elizabeth’s memory was routinely used in support of anti-Catholicism.

★ ★ ★

July 2021:

‘Anniversaries, Bells, Candles, and Drums: The Posthumous Auditory Celebrations of Elizabeth I’

Soundscapes in the Early Modern World Conference

Bells were a frequent sound of celebration in early modern England; they rung out, for instance, after the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1586, and in the aftermath of the failed invasion of the Spanish Armada in 1588. These events in particular were tied up with the myth of Elizabeth I, and as David Cressy has shown, they were celebrated with fervour on 17 November—Elizabeth’s accession day—in the years after the last Tudor monarch’s death. The ring of a bell, however, is only a fleeting auditory moment, although it can take on an eternal quality when its ringing is recorded on paper. These records, however, carried an array of meanings that went beyond the literal sound of the bell’s ring, and early modern readers understood this shorthand. This paper analyses some of the many examples where the ringing of bells was associated with Elizabeth and her return of England to Protestantism, especially in the years after her death. Celebrating Elizabeth’s accession day by the ringing of bells is one thing, but recounting the way bells were rung before and during Elizabeth’s reign in the years after her death arguably served a different, albeit related, purpose.

★ ★ ★

June 2021:

‘From Lamb to Wolf: Elizabeth I and Anti-Catholicism, 1558–1681’

Catholicism and Literary Culture in Scotland, Ireland, and England: Comparative Perspectives Conference

That Elizabeth I of England was an icon of anti-Catholicism in seventeenth-century England is a well-known fact. It is seldom noted, however, that the image of the anti-Catholic Elizabeth of the Exclusion Crisis (1679–1681) is vastly different to the image of Elizabeth as a ‘victim’ of Catholic schemes that was perpetuated at her succession in 1558. This paper explores the way that Elizabeth’s relationship with anti-Catholicism shifted in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, focusing on how the literary depiction of Elizabeth as a passive victim of Catholicism shifted instead to one of an active attacker of Catholics and Catholicism. While this shift is at least partially Elizabeth’s own fault—due to her own increasingly anti-Catholic agenda—the re-printing of her Golden Speech in 1679, for instance, with the fabricated title ‘The last speech and thanks of Queen Elizabeth of ever blessed memory, to her last Parliament, after her delivery from the popish plots’ shows that this shift intensified after her death, and reached new heights within the context of the Exclusion Crisis. By analysing a range of texts, including pamphlets and plays, this paper argues that concerns over the internal and external threats of Catholicism under successive Stuart monarchs meant that writers turned to the monarch who was seen as being responsible for the defeat of the Spanish Armada to show how England had been rewarded by God for its Protestantism, and to highlight the dangers Catholicism posed to England by using Elizabeth as the supreme example of an anti-Catholic warrior.

★ ★ ★

May 2021:

‘When the King is/is not a Woman: Queering Elizabeth I’

Public lecture hosted by queer/disrupt

[Recording of Talk]

★ ★ ★

March 2020:

‘Writing History: Audience, Research, Content’

Talk for students at Sir George Monoux Sixth Form College, Walthamstow

★ ★ ★

October 2019:

Public Lecture: ‘Elizabeth I and Mary Queen of Scots on Film: Allies or Enemies?’

Part of the Research in Arts and Humanities at Manchester Metropolitan University programme

★ ★ ★

October 2019:

‘Female Kingship in Elizabethan England’

Sex and Gender Politics: Medieval and Early Modern Studies Symposium

Thanks to a litany of depictions in popular culture, Elizabeth I of England is widely believed to have struggled for the duration of her reign to be accepted as a female king, with her reign being some kind of aberration that was only ‘successful’ because she had powerful men around her who kept her under control while steering the ship of state on her behalf. Such a view still pervades much of the scholarship on Elizabeth: whether this be a focus on her unwedded and virginal status, her interest in pageantry, or her general indecisiveness and constant desire to prevaricate on almost all political decisions. This is not to say that Elizabeth is not guilty of such criticisms; indeed, she is probably the least decisive monarch to have sat on the English throne since 1066. This paper contends, however, that virtually none of this has to do with either Elizabeth’s sex or gender. Contrary to the modern popular perception, being a female king was not an issue for the English polity or commonwealth: in other words, Elizabeth’s gender did not really matter in sixteenth-century England. This paper unpicks some of the pervading myths surrounding Elizabeth’s exercise of female kingship, arguing that the use of biblical analogy throughout the early modern period demonstrates that sovereignty was not inherently gendered. As she declared in her now-famous Golden Speech of 1601, Elizabeth was England’s king, queen, and prince: her subjects did not find any reason to object to this, so why should we?

★ ★ ★

September 2019:

‘William Shakespeare and Elizabeth I: The Special Relationship?’

Shakespeare on Screen in the Digital Era: The Montpellier Congress

One of the most famous scenes from Shakespeare in Love (1998) is the dramatic reveal near the end of the film that Queen Elizabeth I had secretly been in the audience at the Globe watching the premiere of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. This event is of course entirely fictitious, but it is not an unusual part of cinematic and televisual depictions of the life and work of Shakespeare. At the core of this paper is the question: why do modern adaptations of Shakespeare depict him as having a close, personal friendship with Elizabeth I? Certainly, Elizabeth saw some of Shakespeare’s plays when they were performed at Court—notably The Merry Wives of Windsor and Love’s Labour’s Lost—but it was under her successor, James VI & I, that Shakespeare achieved his greatest successes. Likewise, Elizabeth and Shakespeare would have known of each other, but only in a traditional sense (one knows who the monarch is) and in a professional sense (Elizabeth would have been aware—even vaguely—of who the actors performing at court were). This paper analyses the depiction of the fictitious relationship between Elizabeth and Shakespeare in Upstart Crow (2016–) to argue that this fictional friendship is used to ‘soften’ Elizabeth—that is, to make England’s (in)famous Virgin Queen more ‘human’ and less bizarre, especially in her old age—and because Shakespeare is intrinsically associated with the Elizabethan period, audiences believe he ‘must’ have enjoyed Elizabeth’s patronage. In analysing an adaptation that was produced in the context of the celebrations of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, this paper seeks to understand why audiences are so eager to see these two important figures of the English past as friends.

★ ★ ★

June 2019:

‘Elizabeth the Resilient: Providential Favour and Protestant Polemic in Early Modern England’

Kings and Queens 8: Resilio ergo Regno Conference

The life of Elizabeth I of England is well known, and key events in her reign have been long mythologised and celebrated. Her resilience in the face of potentially traumatic events turned her into a potent national symbol of Protestantism that endured after her death. She survived multiple assassination attempts, recovered from several near-fatal illnesses, and became a focal point of national celebrations in the aftermath of the failed invasion of the Spanish Armada. Elizabeth herself, however, was rarely involved in foiling assassination attempts, nor did she play an active part in the preparations against the Armada. What mattered, however, was that her preservation from these traumatic events was seen as proof of Elizabeth’s providential favour, which in turn helped create what we know today as the ‘Elizabeth myth’. This paper considers three moments of crisis for Elizabeth—the interrogation as part of her assumed complicity in the Wyatt Rebellion under Mary I; the foiled Babington Plot, and the associated treachery of Mary, Queen of Scots; and the attempted invasion of the Spanish Armada—focusing on their use in royal and polemical propaganda in both the latter period of Elizabeth’s reign and into the Stuart period. This paper thus argues that Elizabeth was a beacon of continuity for the Stuart monarchs, and in time, the English celebrated the last Tudor monarch’s recovery and preservation from these moments of national impact as a way of counselling and critiquing their new Stuart kings.

★ ★ ★

April 2019:

‘Entertaining Royal Visitors: Performing the story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba’

Performance, Royalty and the Court, 1450–1800 Conference

Of all the many entertainments, plays, shows, and masques performed before English monarchs, we only know of two that are adaptations of the biblical story of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to the court of King Solomon. Interestingly, these two performances took place when the monarch was hosting a visiting royal: Sapientia Solomonis was performed by the Westminster Boys on 17 January 1566 before Elizabeth I and her visitor, Princess Cecilia of Sweden; and a masque, generally referred to as ‘Solomon and the Queen of Sheba’, was performed at Theobalds in late July 1606 before James VI & I and his visitor, Christian IV of Denmark. That this theme was chosen for the entertainment of a visiting royal is perhaps not a complete surprise, but it does invite numerous questions. For instance, at each performance, the monarch and their visitor were the same gender—what, therefore, were the (gendered) implications of this fact? Likewise, both Elizabeth and James sought to depict themselves as contemporary Solomons, and it seems that these entertainments reflect this desire—but is this the only reading of the entertainments? This paper will therefore consider both the performances of the entertainments, and the religio-political context of the royal visits, to argue that the shows are an exercise in political theatre that was as much about counselling the monarch as entertaining them, while also emphasising the way that biblical stories crossed cultural boundaries. While Elizabeth and James might have been contemporary Solomons, were Cecilia and Christian really like the Queen of Sheba who visited because they ‘heard of the fame of Solomon’? (1 Kings 10:1).

★ ★ ★

April 2019:

‘Elizabeth I, Anti-Popery, and the Exclusion Crisis (1679–1681)’

Representations of Popery in British History Conference

★ ★ ★

July 2018:

‘Kings’ Stomachs and Concrete Elephants: Gendering Elizabeth I through the Tilbury Speech’

Kings and Queens 7: Ruling Sexualities Conference

The speech to the troops at Tilbury is arguably Elizabeth’s most famous. The well-known line—“I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king”—is fairly ubiquitous, and it is routinely included in cinematic and televisual depictions of Elizabeth and her reign. While the historicity of the content of the speech is debated, extant—and nearly contemporary—accounts of the speech do survive. However, and rather curiously, the speech is seldom reproduced as it is survives. This paper argues that the depiction of the Tilbury Speech speaks to the gendered depiction of Elizabeth in the relevant adaption. To the best of my knowledge, no adaption of the speech completely reproduces the surviving text in the letter from Leonel Sharp to the Duke of Buckingham. The reasons for this deviation are (likely) varying, but I argue that the vast majority of the changes reflect the way Elizabeth’s gender has been depicted, and comment on the way writers and directors grapple with Elizabeth’s incongruous position as a female king. This paper will analyse the depiction of the Tilbury Speech in four different adaptions in the past century: in the films Fire Over England (1937) and Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007), and in the television series Blackadder II (1986) and Mapp and Lucia (2014). These four adaptions all depict the Tilbury Speech in different ways; ways, I argue, that reflect the characterisation of Elizabeth and her gender. In analysing these four adaptations, I conclude that while writers and directors seem to have little issue with Elizabeth declaring that she has “the body of a weak, feeble woman,” they seem to stumble on her follow up declaration that she has “the heart and stomach of a king.”

★ ★ ★

July 2018:

‘“As Solomon, so I above all things have desired wisdom”—Elizabeth I, Biblical Analogies, and the Catholic Threat of the 1580s’

Society for Renaissance Studies 8th Biennial Conference

Biblical figures—particularly from the Old Testament—were a key component of Elizabethan royal iconography. As is well established in the scholarship, in her own writings and speeches, and in the polemic tracts of her supporters, Elizabeth was compared with various figures from the Bible. These comparisons with figures such as Deborah, Solomon, David, Daniel, Esther, and Judith all served as a potent religio-political tool: one that simultaneously allowed Elizabeth to demonstrate the divine precedent for a decision (or indeed, lack of decision), while also allowing her subjects to counsel her to emulate the actions of a providentially favoured biblical figure. These biblical analogies, however, also sit beside, and overlap with, the various pagan analogies that were invoked, particularly those between Elizabeth and the classical virgin goddesses. The scholarship generally treats the parallel existence of these two types of analogies as some kind of dilemma, with various hypotheses proposed to explain the purported waxing and waning of these analogies across Elizabeth’s reign, with particular focus on the supposed supplanting of the biblical figures with the classical ones.

This paper argues that the fluctuations of the appearance of an analogy cannot be read as a sign of the figure’s disfavour, or ‘unfashionableness’. Instead, I argue that the invoking of biblical analogies was predominantly tied to a specific event. This paper counters claims of the waning popularity of Elizabeth’s Old Testament biblical analogies in the latter third of her reign by considering the aftermath of the events of 1586 and 1588, arguing that biblical analogies were drawn throughout the entirety of Elizabeth’s reign, but only when the connection made sense.

★ ★ ★

June 2018:

‘Child Actors, Shakespeare, and Skill: Enskilling Child Actors in Elizabethan England’

British Shakespeare Association Conference 2018

The enskillment of child actors was embedded in various productions—both theatrical and civic—over the Elizabethan era. This paper focuses on two methods of enskillment—scaffolding and shepherding—and traces their appearance across the Elizabethan and early Jacobean periods, specifically in: the entertainments performed for Elizabeth in Norwich in 1578; Marlowe’s Edward II, and Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet. This paper lays the groundwork for future research into boy actors by arguing that boy actors in civic entertainments, and those in theatrical productions, complemented and reinforced each other’s skill.

★ ★ ★

April 2018:

‘Kings’ Stomachs and Concrete Elephants: Gendering Elizabeth I through the Tilbury Speech’

Elizabeth I: The Armada and Beyond, 1588 to 2018 Conference

The speech to the troops at Tilbury is arguably Elizabeth’s most famous. The well-known line—“I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king”—is fairly ubiquitous, and it is routinely included in cinematic and televisual depictions of Elizabeth and her reign. While the historicity of the content of the speech is debated, extant—and nearly contemporary—accounts of the speech do survive. However, and rather curiously, the speech is seldom reproduced as it is survives. This paper argues that the depiction of the Tilbury Speech speaks to the gendered depiction of Elizabeth in the relevant adaption. To the best of my knowledge, no adaption of the speech completely reproduces the surviving text in the letter from Leonel Sharp to the Duke of Buckingham. The reasons for this deviation are (likely) varying, but I argue that the vast majority of the changes reflect the way Elizabeth’s gender has been depicted, and comment on the way writers and directors grapple with Elizabeth’s incongruous position as a female king. This paper will analyse the depiction of the Tilbury Speech in four different adaptions in the past century: in the films Fire Over England (1937) and Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007), and in the television series Blackadder II (1986) and Mapp and Lucia (2014). These four adaptions all depict the Tilbury Speech in different ways; ways, I argue, that reflect the characterisation of Elizabeth and her gender. In analysing these four adaptations, I conclude that while writers and directors seem to have little issue with Elizabeth declaring that she has “the body of a weak, feeble woman,” they seem to stumble on her follow up declaration that she has “the heart and stomach of a king.”

★ ★ ★

February 2017:

‘The King, the Queen, the Virgin, and

the Cross: Catholicism versus Protestantism in Elizabeth and Elizabeth: The Golden Age’

Australia and New Zealand Association for Medieval and Early Modern Studies Biennial Conference

The way in which historical films depict conflict often says much more about contemporary issues than it does of those belonging to the period depicted on the screen. Both of Shekhar Kapur’s films about Queen Elizabeth I of England—Elizabeth (1998) and Elizabeth: the Golden Age (2007)—clearly reflect and repurpose contemporary religious tensions. While a film about Elizabethan England cannot avoid engaging with religious politics, this paper argues that Kapur took contemporary religious debates, and repurposed them for his films. This repurposing is visible in the depictions of Catholics and Protestants: Catholics are depicted as evil and scheming—a metaphor for modern religious fundamentalism; whereas the Protestants, embodied by Elizabeth, are depicted as being moderate and secular—people who wish to rise above religious divides, and rule for the common good. This paper will also touch on the racial undertones that influence depictions of different religions and their adherents. Kapur’s films, therefore, should be seen as an attempt to make sense of modern religious fundamentalism and intolerance.

★ ★ ★

November 2016:

‘The Edge of Adulthood: Shakespeare and the Enskillment of Child Actors in Elizabethan England’

Australia and New Zealand Shakespeare Association Biennial Conference

Child actors were an integral part of Elizabethan drama—both in theatrical productions and in civic entertainments. Children played different roles to adults, but often as a way to increase their performative skill. By playing minor roles in performances—such as pageboys and messengers—children gained exposure to the demands of performance, and became more skilled as performers. This enskillment of child actors was embedded in various productions over the Elizabethan era, and throughout the period, the various techniques used in the enskilling became more sophisticated. This paper will focus on two methods of enskillment—scaffolding and shepherding—and trace their development and use through their appearance at the entertainment performed for Elizabeth in Norwich in 1578, in Marlowe’s Edward II, and in Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet. This paper lays the groundwork for future research into boy actors by arguing that the two genres are not divided by the sharp edge that they are routinely seen as having; but rather, that their blurred edges allow us to see the way that they complimented and reinforced each other.

★ ★ ★

July 2016:

‘A Man? A Woman? A Lesbian? A Whore?: Queen Elizabeth I and the Cinematic Subversion of Gender’

International Medieval Congress (Invited Presentation)

Queen Elizabeth I of England appears to suffer from an identity crisis in modern historical films. This identity crisis stems from filmmakers inability to come to a consensus on a characterisation of England’s most depicted monarch. Do they portray her as the famous Virgin Queen? Should she rule like a man? Should she suffer from the ‘weakness’ of the female sex? Should she be able to control the men that surround her? All of these questions are answered—in a variety of both successful and unsuccessful ways—in the historical films of the last forty years that feature Elizabeth. This muddled depiction, however, has resulted in the Queen's gender being both at the fore of her characterisation, and also completely subverted, in order to present the Elizabeth known to popular culture. This inability of filmmakers to fully comprehend Elizabeth and her gender, however, has its roots in her own life. Questions of how to conceive of England's first unmarried, Protestant monarch swirled around the Queen right up until her death: most of which were never answered. Thus, this paper will analyse both how Elizabeth’s gender serves as the central plot complication for most of her cinematic depictions, and also the basis these questions surrounding her gender had in her life.

★ ★ ★

April 2016:

‘“Never mistake a civic pageant for King Lear” – Child Actors’ Skill in Elizabethan Civic Entertainments’

Department of English and Linguistics Seminar Series

★ ★ ★

December 2015:

‘Child Actors’ Skill in Elizabethan Civic Entertainments’

Memory Day 2015: Memory and Skill Across Time Conference

Child actors were a central component of Elizabethan civic entertainments. Children were seen to possess a very particular skillset, which saw their orations contain the substance of the entertainment, and allowed them to make political statements that adults could not make without serious reprisals. During the height of the marriage negotiations between Queen Elizabeth I of England and Francis, the Duke of Anjou, in 1581, child actors delivered key orations in an entertainment performed for the Queen called The Four Foster Children of Desire. The entertainment was a high-pressure, high-stakes event: not only was there a real possibility of the marriage taking place, the audience of the entertainment also included Anjou himself, as well as other French diplomats. In this highly pressured environment, the child actors were also expected to memorise and then recite vast amounts of prose—far more than contemporary civic pageantry usually demanded. This higher expectation of demonstrable skill indicates that the children were highly trained, but not at the level of students of the Elizabethan choir schools, as they were not involved in the performative aspect of the entertainment. The Four Foster Children of Desire therefore demonstrates that skill and memory expectations differed depending on the genre of the performance, and the political aspect of the show.

★ ★ ★

July 2015:

‘“I have become a Virgin” – The Virgin Queen in Film’

Australia and New Zealand Association for Medieval and Early Modern Studies Biennial Conference

Of all the European monarchs, Queen Elizabeth I of England is the subject of the most historical films. Over 20 films feature the Queen as an identified character, and despite their varying storylines (either inspired by historical events or completely fabricated moments), they all include a reference to the same concept: Elizabeth as the Virgin Queen. Shekhar Kapur's 1998 film, Elizabeth, is undoubtedly the most overt in its use of the Virgin Queen iconography. But what is also remarkable is that Elizabeth is the only historical film of the Queen to show her engaging in sexual intercourse. Viewers are thus exposed to the construction of Elizabeth as the Virgin Queen, for they are aware it is not a biological reality. So as to leave no doubt in the audience's mind of the success of the construction, Elizabeth's final line in the film is “I have become a virgin.” This paper will analyse the various constructions of Elizabeth the Virgin Queen that appear in Elizabeth, focusing on how the constructions mirror historical events, and also how these constructions play on popular culture understandings of England's only unmarried female monarch.

★ ★ ★

June 2015:

‘“A great and long voyage” – Princess Cecelia of Sweden's Visit to England in 1565’

Royals on Tour: The Politics and Pageantry of Royal Visits Conference

Crown Prince Erik of Sweden (later King Erik XIV) engaged in multiple marriage negotiations with Queen Elizabeth I of England during his reign. In September 1565, Eric's younger sister, Cecelia, visited England. She had heard much about the English Queen from the marriage envoys, and she was determined to meet the monarch whose hospitality and intelligence had gained her international fame. Cecelia remained in England until April 1566, when her widespread unpopularity and heavy debt forced her to return home. This paper will analyse the key events during Cecelia's eight-month visit, particularly focusing on how the visit of Sweden's princess to the English queen was compared to the Queen of Sheba's progress to the court of King Solomon in the Old Testament.

★ ★ ★

July 2014:

‘“Tonight I think I die” – Elizabethan Religious Conflict and Violence on Film’

Australian Historical Association Conference